Víctor de Currea-Lugo | September 28, 2020

There are several issues in the history of Colombia which obstinately refuse to become part of the reality. One of them is a peace process with the National Liberation Army, ELN. In fact, there have been 29 years of contacts, documents and processes that have not reached a final agreement.

One of the main problems has been the invention of an ELN, which corresponding the dreams of its sympathisers or the fears of its critics. The ELN which exists in reality in the regions of Colombia is a far cry from what the governments imagine in the negotiations. This means they come with a series of suppositions that do not contribute to a real negotiation.

The mythical construction of that ELN is the result of a collective creation, in which everyone has contributed: from the ELN itself by not recognising its own flaws, until the government which magnifies or minimises it, according to its needs, and also academics who study it based on research, conducted by others who also study it on the basis of other texts. Nevertheless, the negotiations will only be possible when the aforementioned parties decide to sit down knowing what the ELN really is.

A second tendency is to neglect the fact that the ELN is not willing to engage in a constructive dialogue which leads, in theory or practice, exclusively to the demobilisation of theirs members. In the case of the FARC, there was a comprehensive agenda that included an agrarian policy, political participation, serious discussions concerning illicit crops and the recognition of victims. As for the ELN, there is an agenda with factual implications. Therefore, expecting that the ELN merely accepts a disarming and demobilisation process is not just naive but also highly irresponsible, in the sense of not understanding the reality that surrounds the ELN.

It is worse still when they expect the ELN to behave like the FARC or completely ignore the string of mistakes, inconsistencies and errors in the implementation of the recent process. To believe that the ELN is going to forget the historic tendency of the elites, to sign agreements and break them, is to ignore the very national reality.

A third element is to observe more at the elenos (i.e. ELN members) and less at the experts on the ELN (elenólogos): the group of people who have specialised in speculating on how to negotiate with the ELN. The Spanish term elenólogos was coined by Pablo Beltrán, a high-ranked guerrilla Commander, to refer disparagingly to those who thought they knew the ELN. On one occasion, the First Commander of the ELN, Nicolás Rodríguez Bautista, stated ironically that the elenólogos knew more about the ELN than its own Central Command.

It can be stated, without fear of exaggeration, that there are also elenophiles: those who are incapable of acknowledging the mistakes and violations of International Humanitarian Law by the ELN such as kidnappings and attacks on oil pipelines. They romanticise this guerrilla group and disregard, for example, its acute faults related to the communities where it has a presence.

But there are also the elenophobes: those who irritatingly find none of the interpretations, acts, explanations or arguments that the ELN provides, as useful. Many of those individuals can be found in the government and also in the peace groups. They are deeply reactive and seem to condemn every communiqué from the ELN, before even reading it. In this sense they are no different, methodologically speaking, from the elenophiles, those who mythicize the insurgency. The elenophobes explain everything on the basis of one part and, as the ELN’s behaviour is very heterodox, they will always find one example with which to justify everything that they seek to condemn outright.

It is true that the real ELN with which they have to negotiate has a degree of unity much greater than it had before its V Congress; there is absolute acceptance of Nicolás Rodríguez Bautista as its first commander, there are internal disputes, as in all human organisations, but that does not mean that there are various ELNs nor that its National Direction is divided. As a structure, which is scattered around the country, it has regional and local dynamics of its own, but this does not mean that the ELN’s negotiating team does not represent its entirety.

The elenophiles attempt to deny the sometimes-serious tensions between the civilian population of certain regions and the military structures of the insurgency; or they minimise the environmental impact of some of its actions. Thus, denying the impact of degrading practices, war crimes or links to drug trafficking is not helpful in properly understanding the read possibilities of moving forward to a peace process.

The real ELN has a red line for negotiations: namely, the constant participation of civil society. There are too many proposals and concrete approaches to it, to believe that it is some unachievable utopia, as some have stated when quickly discounting it.

But it is not enough to have some pre-established mechanisms and to accept the actor with which a dialogue will be held, if there is no political will. For some, the debate is whether the glass is half full or half empty, but the correct question is whether the glass exists at all; call it a «glass», in this case, the political will.

What has been noticed in the first two years of Duque’s government is that there is no real concrete and effective interest in moving forward to negotiations with the ELN, not even in a populist fashion in order to improve its popularity or maintain links with the international community, either in order to pretend before the UN that it has such a will.

Over the last two years, a significant number of messages, communiqués and calls for peace with the ELN, to resume the negotiations and re-establish the process have been made: but all of it has been unviable. And it was impractical not due to minor or circumstantial items, but because there is a clear political decision that makes it impossible to move forward.

There are even those who have proposed starting from zero and begin, again, an exploratory phase, but this is not the solution, not only because it implies disregard and removal an advanced process, but also because this would not lead to the negotiating talks being started, just like the unilateral truces and release of kidnapped persons by the ELN did not.

The truces made by the ELN, its release of some kidnapped individuals, as well as the gestures from civil society, the calls from the Pope for a ceasefire in the midst of the pandemic and even those from the UN have had no response from the government. It is curious but the elenophobes have managed to establish a narrative in which after each proposal that the government does not comply with they have an argument to blame the ELN for the failure of the attempt to move forward and restart the talks.

So what then is left? Given the current situation, the most we can hope for is the humanisation of the war: protecting civilians through the application of the Geneva Convention. This is precisely what the Humanitarian Accord, Now! in Chocó has sought; the proposal Humanitarian Minimums in Arauca or the Humanitarian Demining project in Nariño; three proposals in zones of ELN influence.

The Duque government and the ELN make the same mistake that is substituting political discourse for armed actions. This not only leads to an increase in hostilities but rather a fundamental problem: the negation of a more political space for the exchange of ideas, the strengthening of a society well-disposed to peace and the search for paths of negotiation. At the same time as calling for humanitarian norms, it strengthens a civil society that accompanies the peace, the revision of proposals for a how to negotiate and a critical but informed view of the nature of the ELN.

This means studying the ELN in its entirety and not defining it on the basis of one of its parts. It also means being able to recognise the lack of will in Duque government to move forward with the process. Furthermore, it means having a critical discussion on how a society in favour of peace perceives the ELN, as it is impossible to want to be a valid facilitator of a process without acknowledging the unity of the ELN and its will for peace and without generally giving it some credibility. Asking for unilateral gestures or producing documents seeking only what one activist described in a meeting as «cornering the ELN» is not only naive but useless.

The elenophiles also have to contribute to this guerrilla organisation understanding that peace negotiations, such as that which was proposed in Ecuador, would not seek to defeat the elites at the negotiating table but rather to win over society through political activity. This means being a political and not just a military actor.

So whilst applauding all the small, medium and large efforts to restart the process, the blockage is not with the efforts themselves but in the political will. And the political will of the government does not exist. At the same time the ELN has to answer before its own members and not the general public whether that mandate of the V Congress to «explore peace» still stands. If this is not the case, it faces a strategic problem: the future of its programme in the midst of a war that it clearly cannot win. But if it continues with its programme to explore peace, this should be accompanied by debates and convictions that lead it to talk to the country, not only through military actions but rather through more audacious proposals.

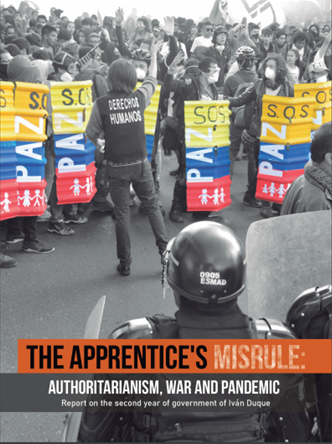

Article published in: THE APPRENTICE’S MISRULE. Authoritarianism, war and pandemic. Bogotá, 2020. Versión en español disponible en: El futuro de la negociación Gobierno-ELN